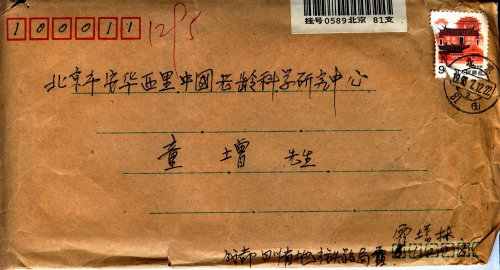

Date of letter:1993-03-10

Address of author:Chengdu City, Sichuan Province

Date of event:1938-1943

Location of event:Jingxing County, Shijiazhuang City, Hebei Province

Name of author:Huo Peilin

Name(s) of victim(s):Huo Peilin’s sister and father

Type of atrocity:Rapes, Others, Slave Laborers(RA, OT, SL)

Other details:In late 1938, the Japanese invaded the Zhoujiakeng Village, burning, killing and looting. Huo Peilin’s sister, refused to hide with the folks worring that her child’s crying would expose their hiding place and was raped by Japanese. In 1941, in the event of a gas explosion during coal mining, the Japanese capitalists sealed the escape holes for more than three thousand people with cement, in order to avoid the spread the gas. In 1943, Huo Peilin’s father was beaten by Japanese for picking up their thrown-away shoes, and died the next day. The letter has stamped proof of Sichuan Province Transport Association.

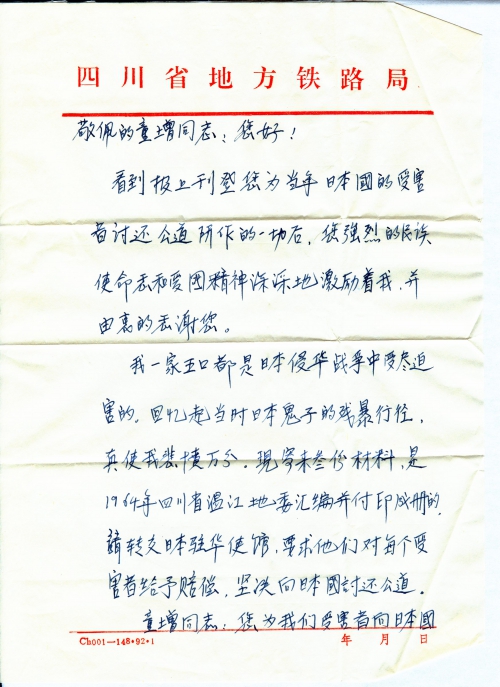

Respectable comrade Tong Zeng,

After reading the newspaper article about you pursuing justice for Chinese victims of Japan’s war of aggression against China, I am greatly inspired by your strong sense of national mission and patriotism and I’d like to express my sincere gratitude to you.

My 5-member family suffered a lot from the war. It really hurts to recall the atrocities of the Japanese army. I am sending three pieces of material that were compiled and printed by the Party Committee of Wenjiang, Sichuan Province in 1964. Please forward them to the Japanese embassy in China and firmly demand justice and compensation for each victim from China.

Comrade Tong Zeng, your full devotion to demanding compensation from Japan for victims like me inspires my respect. Thank you again.

Wish you success and luck with everything.

Local Railway Bureau, Sichuan

Huo Peilin

March 10, 1993

Postal code: 610081

Tel: 338620

781072

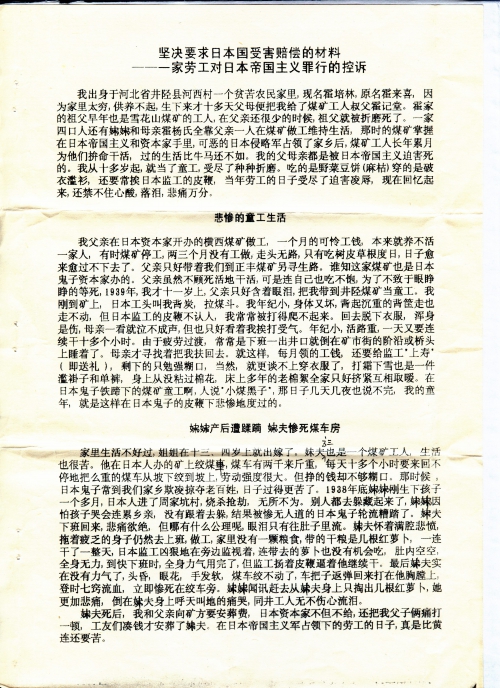

Firmly Demanding Damage Compensation from Japan

-A Family of Slave Laborers Charge Japanese Imperialism with Crimes

I am Huo Peilin, originally Huo Laixi, and was born into a poor farmer’s family in Hexi Village, Jingxing County, Hebei Province. As my parents were too poor to raise me up, they gave me to my uncle Huo Jitang, a coal mine worker, about a dozen days after I was born. My grandfather was also a worker of Xuehuashan Coal Mine in his early years, but was tortured to death when my father was still young. My whole 4-member family, including my older sister and mother Mrs. Huo, née Yang, depended on my father working in a coal mine. Back then, the mines were in the charge of Japanese imperialists and capitalists after the vicious invading Japanese army occupied my hometown. The mine workers worked their fingers to the bone for many years, but lived a life worse than animals. Both of my parents were persecuted to death by Japanese imperialists. I had become a child laborer since I was a little over 10 years old and experienced all kinds of suffering. I ate wild herbs and soybean pancakes (sesame residues), was dressed in rags and was often whipped by Japanese foremen. I still cannot help but feel sad and cry when recalling the suffering and hardships I had as a slave laborer.

Miserable life as a child laborer

My father worked in Hengxi Coal Mine run by a Japanese capitalist and was paid too little to support my whole family. Sometimes the mine would be shut down and my father would have no work to do for 2 or 3 months. We had no choice but eat tree barks and grass roots. Life couldn’t go on like this. So my father took us along and found a job in Zhengfeng Mine to make a living. Unexpectedly, it was also run by a Japanese capitalist! Even though my father worked desperately, he couldn’t earn enough food for himself. To prevent my family from waiting for death, my father, with tears in his eyes, had to bring me to Jingxing Coal Mine to be a child laborer in 1939 when I was only 11 years old. Just after I joined the mine, I was ordered by a Japanese foreman to carry coal and pull coal buckets. I was too young and too weak to walk while carrying the heavy basket, but the whips of the Japanese foremen equally fell on all laborers. I often had difficulty getting up after being whipped to the ground. After I returned home and took off clothes, my bruises all over the body made my mother cry, but she couldn’t do anything about it. Due to a young age and heavy work for over 10 hours straight in a day, I was so exhausted that I often fell asleep on the stairs in the Kuangshi street or under the bridge as soon as I got off work. Then, my mother would search for me and carry me back. Even so, our monthly wages, except a “gift” (bribery) to the foremen, could barely support our family, let alone buy new clothes. We wore ragged coats and thin clothes even in cold winter and never had any cotton on us. The whole family shared the many-year-old cotton quilt for warmth. The suffering of child laborers working in a coal mine run by the Japanese couldn’t be fully described in days. I spent my miserable childhood under the whip of the Japanese.

Sister was raped after childbirth and brother-in-law died tragically in a mine room

As my family lived a difficult life, my older sister married at the age of 13 or 14 to reduce our burden. My brother-in-law was also a coal mine worker and lived a difficult life. He pulled a coal cart in a mine run by the Japanese. The coal cart weighed about 1,000 kg and he had to pull it up a hill non-stop for over 10 hours a day. Despite heavy work, he couldn’t earn enough money to feed the family. At that time, the Japanese soldiers often came to my hometown to bully the common people, making our life more difficult. In 1938, over a month after my sister gave birth to a child, the Japanese soldiers came to Zhoujiakeng Village to commit all kinds of crimes. All the other villagers hid away, but my sister didn’t follow them for fear that the child’s crying might get them in trouble. Sadly, she was raped in turn by the cruel Japanese soldiers. My brother-in-law was extremely grieved at the news after getting home from work. But how could they get justice? They just had to swallow the pain. My brother-in-law, filled with indignation and exhaustion, still had to go back to work. Since there was no grain at home, he took several red carrots with him. But he worked a whole day without the time to eat them because the vicious Japanese foremen were always monitoring him. He had used up all his strength when it was almost time to get off work, but the foreman whipped him and forced him to continue working. At last, my brother-in-law had no strength left. He felt dizzy and faint and couldn’t pull the coal cart anymore. So the cart sprang back and hit his chest, instantly killing him. After hearing the news, my sister hurried to the site and only took out several carrots from his pocket, which made her sadder. She fell on my brother-in-law and cried her heart out. All the other workers on the site shed tears.

After the death of my brother-in-law, my father and I asked for funeral fees from the mine, but the Japanese capitalists not only refused to pay us, but gave us a hard beating. In the end, the other workers pooled enough money to bury my brother-in-law. The life of slave laborers under the occupation of the Japanese imperialist army was so miserable!

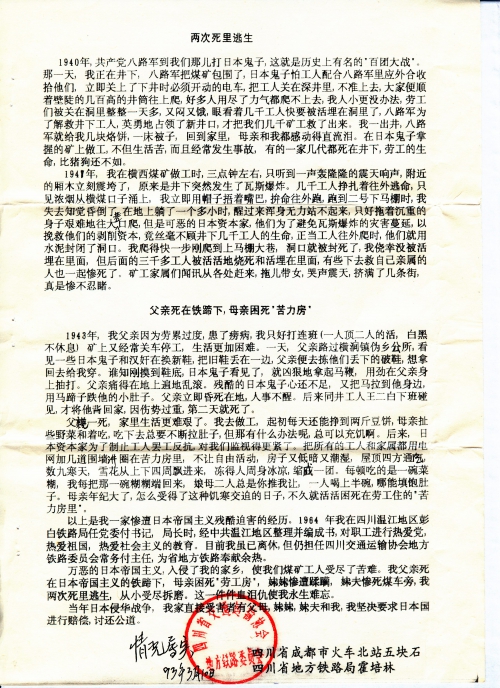

Two narrow escapes

In 1940, the Communist Eighth Route Army fought the historically famous battle- the Hundred–Regiment Campaign-with the Japanese army in my hometown. On that day when I was working down the mine, the Eighth Route Army suddenly surrounded the mine. The Japanese were afraid that the workers might cooperate with the Eighth Route Army to fight them, so they shut down the tram that must be used to get up or down the mine to keep the workers down in the deep mine. The adults tried to climb up the several-hundred-meter-high wall, but in vain, let alone me who was much younger. We were left in the mine for more than one day, suffocated and starved. Seeing that thousands of workers were to be buried alive in the mine, the Eighth Route Army bravely took control of a new exit and saved us all. As soon as I got out of the mine, the comrades with the Eighth Route Army gave me several pancakes and a quilt. When I brought them home, my mother and I were so moved that we cried. Apart from a difficult life, accidents often happened in a mine run by the Japanese. I knew that some family members of several generations died under the mine. The life of slave laborers was indeed more worthless than animals.

At about 3 p.m. on a day in 1941, when I was working for Hengxi Coal Mine, I heard a thunderous boom and nearby crates instantly fell apart. It turned out to be a gas explosion. Thousands of people struggled to escape. Seeing that thick smoke was surging from the hole, I immediately covered my mouth with a hat and ran outside desperately. But I blacked out when I reached No.2 Xiamapeng. After lying on the ground for over an hour, I woke up, but couldn’t stand up due to lack of strength, so I dragged myself towards Daxiangkou. Tragically, to avoid the spread of gas and reduce their losses, the vicious Japanese capitalists sealed the exit with cement without giving a damn to the life of thousands of people under the mine. I climbed fast. When I just reached Mapengdaxiang, the exit was sealed off, so luckily I wasn’t buried alive in there. However, over 3,000 workers behind me were burned or buried alive along with some of their family members who went down to save them. After getting the news, the family members, including children, of the workers hurried to the mine and filled several streets, crying loudly. It was indeed a tragic sight to see.

Father died tragically in the hands of the Japanese and mother was tortured to death in the Laborer House

In 1943, as my father suffered from tuberculosis due to excessive exhaustion, I had to work two consecutive shifts (I did the work of two workers without sleep day or night). Besides, the mine was often shut down. So, our life became harder. One day when my father passed the Puppet Office of Hengjian Town, he saw some Japanese soldiers and traitors putting on new shoes with their old ones thrown nearby. So my father went to pick up their worn-out shoes, intending to take them home for me to wear. Unexpectedly, as soon as he touched the shoes, the Japanese soldiers saw him and took up horse whips to beat him. My father rolled on the ground painfully. But the cruel Japanese soldiers were not satisfied. They pulled a horse near my father and let the horse kick his stomach with its hooves. My father blacked out and became unconscious. Later he was seen by Wang Eerbai on his way home from work in the same mine and carried home by him. Due to severe injury, my father died the next day.

Our life became even harder after my father’s death. At first, I could earn 1 kg bean pancakes by working in the mine and my mother could plunk some wild vegetables to go with the pancakes. Although eating them together always caused diarrhea, it could at least stave off hunger. Afterwards, to prevent the workers from striking or revolting, the Japanese capitalists monitored us more closely. The Japanese kept all workers and their family members in a house with fences and wires and prohibited us from free activities. The house was low, dark and damp with an open roof. In freezing winter, with the snowflakes falling in from all directions, we had to curl ourselves up in a ball. We ate a bowl of vegetable paste for each meal. Every time I brought it back, my mother and I would insist on letting the other one eat it all for a while and then we each would eat half of the bowl. But how could it allay our hunger? My mother couldn’t stand the cold and hunger due to an old age and soon died in the Laborer House.

The above are facts about my family’s suffering caused by the Japanese imperialists. In 1964, when I served as deputy Party secretary and director of Pengbai Railway Bureau, Wenjiang, Sichuan, my family’s history was compiled into a book by the CPC Wenjiang Committee to educate the staff to love the Party, the motherland and socialism. Although I have retired, I still serve as a deputy standing director of the Local Railway Committee of the Sichuan Transport Association to contribute to the local railway industry.

The vicious Japanese imperialists invaded my hometown and made mine workers like me suffer greatly. My father died in the hands of Japanese imperialists, my mother was tortured to death in the Laborer House, my sister was tragically raped, my brother-in-law died miserably near a coal cart and I myself had two narrow escapes and suffered a lot since I was little. I will never forget these debts.

My parents, sister, brother-in-law and I myself are direct victims of Japan’s war of aggression against China. I firmly demand justice and compensation from Japan.

The above facts are true.

Local Railway Committee of the Sichuan Transport Association (seal)

March 10, 1993

Wukuaishi, North Railway Station, Chengdu, Sichuan

Huo Peilin, Local Railway Bureau, Sichuan

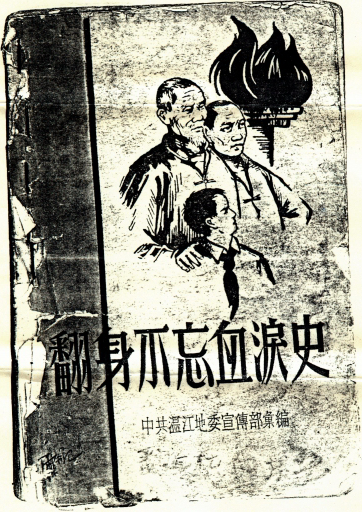

Past Miserable Experiences Not Forgotten after the People’s Liberation

Compiled by Publicity Department of CPC Wenjiang Committee

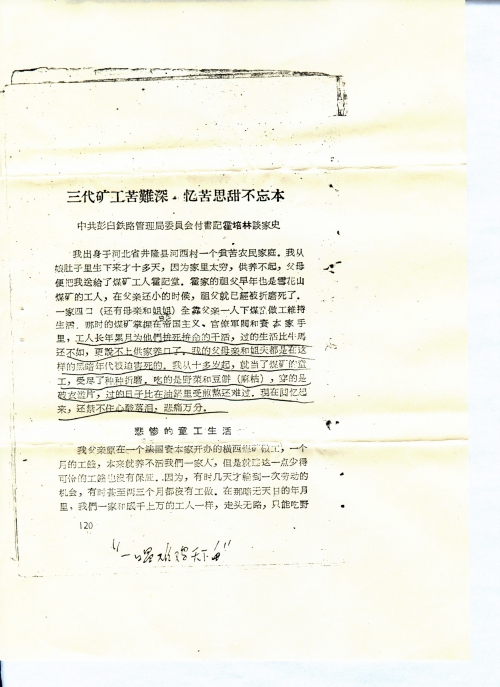

The Suffering of Mine Workers of Three Generations Taught Us to Always Remember the Past Difficulties in A New, Happy Society

Huo Peilin, deputy director of CPC Pengbai Railway Bureau Committee, talks about his family history.

I was born into a poor farmer’s family in Hexi Village, Jingxing County, Hebei Province. As my parents were too poor to raise me up, they gave me to my uncle Huo Jitang, a coal mine worker, about a dozen days after I was born. My grandfather was also a worker in Xuehuashan Coal Mine in his early years, but was tortured to death when my father was still young. My whole 4-member family, including my older sister and mother, depended on my father working in a coal mine. Back then, the mines were in the charge of Japanese imperialists, bureaucrats, warlords and capitalists. The mine workers worked their fingers to the bone for many years, but lived a life worse than animals, let alone support the family. Both of my parents and brother-in-law were persecuted to death in such a dark age. I had become a child mine worker since I was a little over 10 years old and experienced all kinds of suffering. I ate wild herbs and soybean pancakes (sesame residues), was dressed ine rags and lived a miserable life. I still cannot help but feel sad and shed tears when recalling those memories.

Miserable life as a child laborer

My father originally worked in Hengxi Coal Mine run by a French capitalist. His monthly wage was not only too little to support the whole family, but was unstable because he would sometimes be given the chance to work in days or sometimes had no work to do for 2 or 3 months. In the dark age, my family had no choice but eat wild vegetables and tree barks like thousands of other workers like us. As the life became harder and harder, my father took us along and found a job in Zhengfeng Coal Mine run by northern warlord Duan Qirui. We thought our life would become better. Yet, evil people are the same all over the world! Even though my father worked desperately, he couldn’t earn enough food for himself. To prevent my family from being starved to death, my father, with tears in his eyes, had to bring me to Jingxing Coal Mine to be a child laborer in 1939 when I was only 11 years old. My mother couldn’t bear to let me suffer and cried quietly at night. But what choice did we have? After all, a miserable life as a child laborer was better than being starved to death at home! Just after I joined the mine, I was ordered by a Japanese foreman to carry coal and pull coal buckets. I was too young and too weak to walk while carrying the heavy basket, but the whips of the Japanese foremen equally fell on all laborers. I often had difficulty getting up after being whipped to the ground. After I returned home and took off clothes, my bruises all over the body made my mother cry, but she couldn’t do anything about it. Due to a young age and heavy work for over 10 hours straight in a day, I was so exhausted that I often fell asleep on the stairs in the Kuangshi street or under the bridge as soon as I got off work. Then, my mother would search for me and carry me back. Even so, our monthly wages, except a “gift” (bribery) to the foremen, could barely support our family, let alone buy new clothes. We wore ragged coats and thin clothes even in cold winter and never had any cotton on us. The whole family shared the many-year-old cotton quilt for warmth. My suffering couldn’t be fully described in days. In this way, I spent my miserable childhood.

Brother-in-law died tragically near a coal cart

As my family lived a difficult life, my older sister married at the age of 13 or 14 to reduce our burden. My brother-in-law was also a coal mine worker and lived a difficult life. He pulled a coal cart in a mine. The coal cart weighed about 1,000 kg and he had to pull it up a hill non-stop for over 10 hours a day. Despite heavy work, he couldn’t earn enough money to feed the family. At that time, the Japanese soldiers often came to my hometown to bully the common people, making our life more difficult. In the second half of 1938, over a month after my sister gave birth to a child, the Japanese soldiers came to Zhoujiakeng Village to commit all kinds of crimes. All the other villagers hid away, but my sister didn’t follow them for fear that the child’s crying might get them in trouble. In the end, the cruel Japanese soldiers burned my sister’s cottage. My brother-in-law was extremely grieved at the news after getting home from work. But how could they get justice? They just had to swallow the pain. My brother-in-law, filled with indignation and exhaustion, still had to go back to work. Since there was no grain at home, he took several red carrots with him. But he worked a whole day without the time to eat them because the vicious Japanese foremen were always monitoring him. He had used up all his strength when it was almost time to get off work, but the foreman whipped him and forced him to continue working. At last, my brother-in-law had no strength left. He felt dizzy and faint and couldn’t pull the coal cart anymore. So the cart sprang back and hit his chest, instantly killing him. After hearing the news, my sister hurried to the site and only took out several carrots from his pocket, which made her sadder. She fell on my brother-in-law and cried her heart out. All the other workers on the site shed tears.

After the death of my brother-in-law, my father and I asked for funeral fees from the mine, but the capitalists not only refused to pay us, but fired us. To make a living, my father went to a foreign place to do hard labor. My mother and I had no choice but return to Hengxi Coal Mine, bringing with us a little amount of rice left by my father. When we reached Hengxi, a problem came up: where did we live? After asking many people for help, we finally found a damaged cave on the right of the Temple of the God of Plague and temporarily settled down. Later, thanks to the help of our neighbor Uncle Wang Shuanzhu, I could work in Hengxi Coal Mine. Every day, I could earn and bring 1kg bean pancakes (sesame residues) home to go with wild vegetables. In this way, my mother and I were barely kept alive. When it was almost Spring Festival, my father came back. He was terribly tortured, but brought no money home and even the clothes he wore when leaving became rags. Despite a reunion, the whole family had nothing to say to each other, but cried together. When rich people were enjoying fine food and wine accompanied by the joy sound of fireworks, my family even didn’t have rice to cook! At last, Uncle Wang lent us 1.5kg or 2kg bean and elm bark flour so we didn’t starve on the first day of a new year. The life of poor people was so miserable!

Two narrow escapes

In 1940, the Eighth Route Army led by the Communist Party fought the historically famous battle- Hundred–Regiment Campaign-with the Japanese army in my hometown. On that day when I was working down the mine, the Eighth Route Army suddenly surrounded the mine. The Japanese were afraid that the workers might unite with the Eighth Route Army to fight them, so they shut down the tram that must be used to get up or down the mine to keep the workers down in the deep mine. The adults tried to climb up the several-hundred-meter-high wall, but in vain, let alone me who was much younger. We were left in the mine for more than one day, suffocated and starved. Seeing that thousands of workers were to be buried alive in the mine, the Eighth Route Army bravely took control of a new exit and saved us all. At that time, the Eighth Route Army also had a difficult life, but they managed to hand out a large amount of food, clothes and quilts to help us. As soon as I got out of the mine, the comrades with the Eighth Route Army gave me several pancakes and a quilt. When I brought them home, my mother and I were so moved that we cried.

In the old society, mine workers didn’t only live a difficult life, but faced huge risks. Accidents often happened in the mine, causing the death of countless people. Some family members of several generations died under a mine. The life of slave laborers was indeed more worthless than animals.

At about 3 p.m. on a day in 1941, when I was working for Hengxi Coal Mine, I heard a thunderous boom and nearby crates instantly fell apart. It turned out to be a gas explosion. Thousands of people struggled to escape. Seeing that thick smoke was surging from the hole, I immediately covered my mouth with a hat and ran outside desperately. But I blacked out when I reached No.2 Xiamapeng. After lying on the ground for over two hours, I woke up, but couldn’t stand up due to lack of strength, so I dragged myself towards Daxiangkou. Tragically, to avoid the spread of gas and reduce their losses, the vicious Japanese capitalists sealed the exit with cement without giving a damn to the life of thousands of people under the mine. I climbed fast. When I just reached Mapengdaxiang, the exit was sealed. Luckily I wasn’t buried alive in there. However, over 3,000 workers behind me were burned or buried alive along with some of their family members who went down to save them. After getting the news, the family members, including children, of the workers hurried to the mine and filled several streets, crying loudly. It was indeed a tragic sight to see. The indifferent capitalists caused great indignation of other surviving workers. It wasn’t until we launched a strike under the leadership of the underground Party that the capitalists were forced to hold a memorial meeting and pay meager compensation. Life was so hard for the poor in a place where evil people ruled.

Father died tragically in the hands of the Japanese and mother was tortured to death in the Laborer House

In 1943, as my father suffered from tuberculosis due to excessive work, I had to work two consecutive shifts (I did the work of two workers without sleep day or night). Besides, the mine was often shut down. So, our life became harder. One day, my father went to Hengjianguan to pay a visit to a laborer of landlord Yan Hongbang, intending to ask him about whether he could do odd jobs at the landlord’s. When my father passed the Puppet Office of Hengjian Town, he saw some Japanese soldiers and traitors putting on new shoes with their old ones thrown nearby. So my father went to pick up their worn-out shoes, intending to take them home for me to wear. Unexpectedly, as soon as he touched the shoes, the Japanese soldiers saw him and took up horse whips to beat him. My father rolled on the ground painfully. But the cruel Japanese soldiers were not satisfied. They pulled a horse near my father and purposefully let the horse kick his stomach with its hooves. How could my ill father stand such brutal beating! My father instantly blacked out and became unconscious. Later he was seen by Wang Eerbai on his way home from work in the same mine and carried home by him. Due to severe injury and the lack of treatment as we had no money, my father died the next day.

When my father was dying, Wang Jinzhu, the head of the Puppet Village Office, came to our house with his followers and forced my father to dig a ditch around the village. My mother pleaded, “He was badly beaten and is dying. Could he go later?” The followers viciously said, “He has to work even though he is dying.” They looked around our house, but couldn’t find any valuable things. So they left for another house while cursing all the way out. Before my father died, he held my hand and said intermittently, “I don’t leave anything for you…These bad guys will pay for what they have done sooner or later.”

Our life became even harder after my father’s death. At first, I could earn 1 kg bean cake by working in the mine and my mother could plunk some wild vegetables to go with the cakes. Although eating them together always caused diarrhea, it could at least stave off hunger. Afterwards, to prevent the workers from striking or revolting, the Japanese capitalists monitored us more closely. The Japanese kept all workers and their family members in a house with fences and wires and prohibited us from free activities. The house was low, dark and damp with an open roof. In freezing winter, with the snowflakes falling in from all directions, we had to curl ourselves up in a ball. We ate a bowl of vegetable paste for each meal. Every time I brought it back, my mother and I would insist on letting the other one eat it all for a while and then we each would eat half of the bowl. But how could it allay our hunger? My mother couldn’t stand the cold and hunger due to an old age and soon died in the Laborer House.

Reflecting on the past to never forget my origins and never change who I am

Recalling the memories always fills me with tears. But in the dark age, not just me or my family suffered. Before the People’s Liberation, the evil social system tore numerous families apart and caused them homeless. It wasn’t until the People’s Liberation that the Communist Party and Chairman Mao saved us from the miserable life and we poor people began a new life. I grew up under horse whips, but after I joined the revolution, the Party cared about me like a loving mother, taught me the truth of revolution, and helped me on the way towards the People’s Liberation. With the training and education of the Party, my class consciousness improved constantly. Later, I honorably joined the Communist Party of China. Like many comrades, I was a mine worker looked down upon by others in the old society, but now I become the owner of my own life. The Party even appoints me as a leader of a company. When I examine myself, I realize I have so much to do! Especially in recent years, instead of studying hard, having a strong sense of class, resisting the invasion of bourgeois ideology, working conscientiously and hard, and endeavoring to build a good socialist company, I have adopted a certain bureaucratic, decentralized and extravagant style and have undermined the ownership by the whole people to some extent, causing unnecessary losses to the Party’s cause. It really breaks my heart! I feel rather ashamed when reflecting on the past, so I am determined to study hard, actively exercise, take a firm proletarian stance, resolutely establish the communist outlook on life and make efforts to always be a good son of the working people and an outstanding communist fighter who never forgets his origins and never changes who he is!