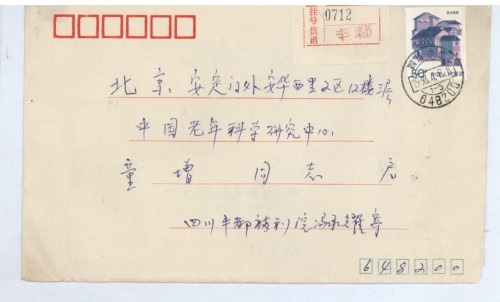

Date of letter:1993-04-08

Address of author:Fengdu County, Chongqing (Fengdu County, Sichuan Province)

Date of event:1944-09

Location of event:Fengdu County, Chongqing (Fengdu County, Sichuan Province)

Name of author:Feng Chengyao(former name Wen Ruo lin)

Name(s) of victim(s):Feng Chengyao

Type of atrocity:Slave Laborers(SL)

Other details:In the summer of 1944, a company recruited people from poor families, and I was one of them. They took us to a warehouse and shut us in it. After a difficult journey, we were escorted to Japan. Since then, we lived a dog’s life. Every day we did heavy manual work, but did not have enough to eat. Due to insufficient nutrition for a long time, it was easy for us to get sick. In winter, we still had to wear thin clothes. More and more people died of disease, so the Japanese soldiers burned the bodies. Our peers died one by one. In Japan, we were cruelly tortured physically and psychologically. I believe that many of the victims would agree with me. The Japanese government must compensate us for all the losses.

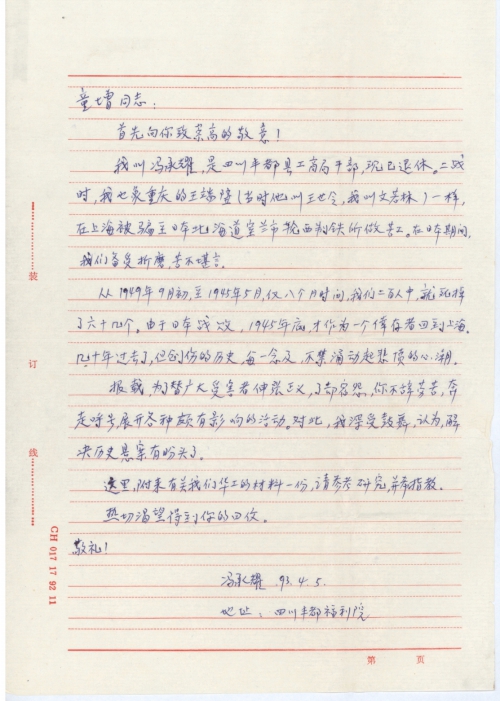

Comrade Tong Zeng:

First of all, lofty salute to you!

I am Feng Chengyao, a retired cadre from the Trade and Industry Bureau of Fengdu, Sichuan. During World War II, I was deceived in Shanghai to become a laborer for Wanishi Iron & Steel Manufacturing Company in Muroran, Hokkaido, Japan, just like Wang Duanbi of Chongqing (then he was called Wang Shiling and I was called Wen Ruolin). We were tormented and suffered unspeakable pain in Japan.

Over 60 out of 200 laborers died in only 8 months from early September 1944 to May 1945. In late 1945 after Japan was defeated, I returned to Shanghai as a survivor. It has been dozens of years, but I still cannot help but feel indignant whenever I recall the painful memories.

It is reported that you have gone through a lot to pursue justice for large numbers of victims, settle their unresolved scores, campaigned and launched various influential programs. I am greatly inspired by you and think that there is hope to solve historic issues.

Attached is a document about Chinese laborers for your reference and guidance.

Really looking forward to your reply.

Best regards,

Feng Chengyao

April 5, 1993

Address: Social Welfare Institution, Fengdu, Sichuan

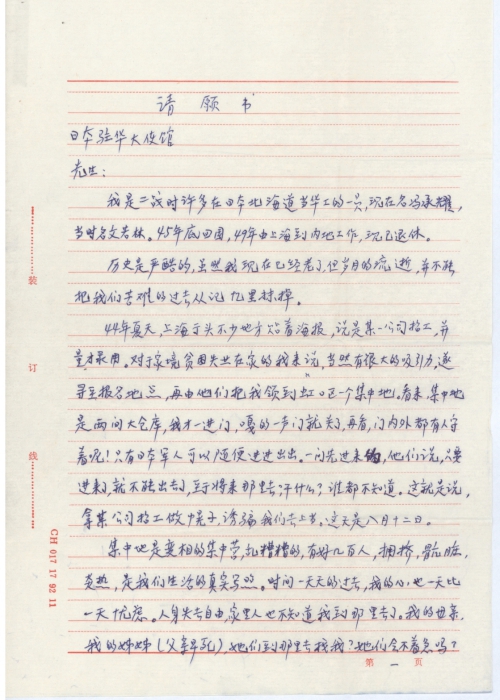

Petition

Mr. Ambassador of the Japanese Embassy in China,

I was one of the many Chinese laborers in Hokkaido, Japan during World War II. My current name is Feng Chengyao and my name was Wen Ruolin when working as a laborer in Japan. I returned to China at the end of 1945, was transferred to work in Sichuan from Shanghai in 1949 and I am retired now.

The history is cruel. Although I am an old man now, the passing of time fails to remove painful past memories.

In the summer of 1944, there were many posters in the streets of Shanghai, announcing that a company is recruiting employees on the basis of their ability. It had strong appeal to me as my family was poor and I was unemployed at that time. So I went to the registration address and was taken to a gathering place in Hungkou District, where there appeared to be two large warehouses. The door was closed as soon as I got in. Then I found that the door was guarded both inside and outside the door and only Japanese soldiers could get in and out at will. I asked those who got in there before me and they told me that we could not get out once we got in and that no none knew where we would be going or what we would be doing. In other words, we were cheated by a ruse in the name of recruiting employees for a company in order to trap us. That day was August 12.

The gathering place was a concentration camp in disguise. There were several hundred people in the camp. It was crowded, filthy and hot. I became more and more anxious as time went by. I was not allowed to leave and my family did not know where I was. Where would my mother and elder sister (my father died early) go to find me? Would they not worry about me? Would they not sleep or eat because of my disappearance? I dare not think further.

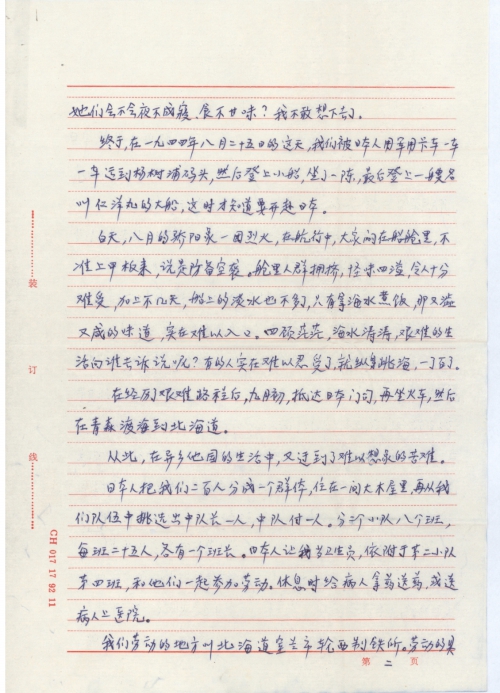

Finally, on August 25, 1944, we were taken in military trucks by the Japanese to Yangshupu dock, where we boarded small boats. After a while, we boarded a large ship named Jin-yo-maru. It was not until then that we realized we would be sent to Japan.

In August, the sun was like a ball of fire in the day time. During the voyage, we were kept in the cabins and were not allowed to get on the deck to supposedly avoid air raids. It was crowded, smelly and very uncomfortable in the cabin. Several days later as we were running out of freshwater, seawater was used to cook. The meals were bitter, salty and unpalatable. But we were at sea. Who could we complain to? Some people could not stand the suffering and jumped into the sea and ended their lives.

After a difficult journey, we arrived in Moji, Japan in early September, took a train to Aomori and then boarded a ship to cross the sea to Hokkaido.

Afterwards, we began to experience unimaginable suffering in a foreign country.

We 200 people lived in a large wood house. The Japanese selected a captain and a lieutenant from our group and divided us into 2 contingents of 8 classes. Each class had 25 people and 1 monitor. The Japanese made me a health worker in Class 4 of Contingent 2. I would labor with them and when at rest, I would procure and send medicine to patients or take them to the hospital.

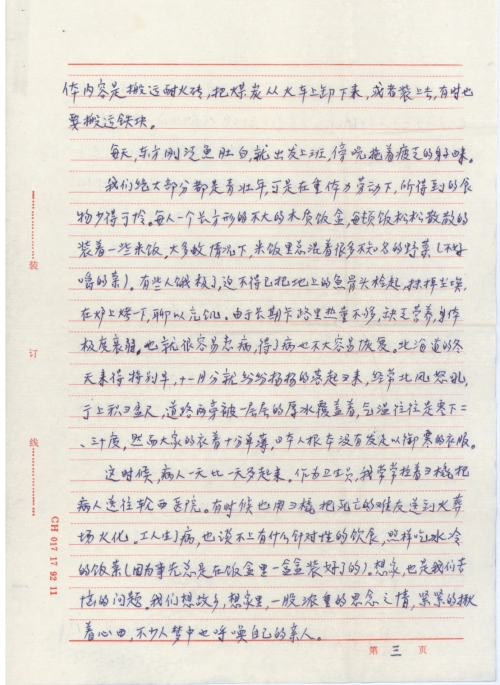

The place where we worked was called Wanishi Iron & Steel Manufacturing Company, Muroran, Hokkaido and our job was to move firebrick and iron and load coal onto or unload it off the trains. Sometimes we had to move iron blocks.

Every day, we started working very early in the morning and got off from work at dusk, exhausted when we got back.

Most of us were young. But we were provided with little food despite heavy physical labor. Each of us was given a small rectangular wooden box with some loose rice grains mixed with unknown wild vegetables (tough to chew) in it most of the time. Some laborers were so hungry they would pick up fish bones from the ground, wipe off the dust, roast them in the oven and eat them. Due to a long-term lack of calories and nutrition, we were extremely weak, likely to get ill and less likely to recover from illness. Winter came early in Hokkaido. Snow fell in November, with wind roaring from the north. The streets were covered with feets of snow and the paths along the streets were covered by thick layers of ice. The temperature was often minus twenty or thirty degrees. However, we still wore thin clothes because the Japanese did not provide us with enough clothes to withstand the cold.

That was when the number of patients increased. As a health worker, I often sent patients on a sleigh to Wanishi Hospital and sometimes dead laborers to the crematory. When the laborers got sick, they still eat cold meals instead of being provided with special meals (because the meals were put in boxes in advance). Homesickness also bothered us. We thought about our hometown and family. Homesickness made us anxious. Not a few people called family members’ names in their dreams.

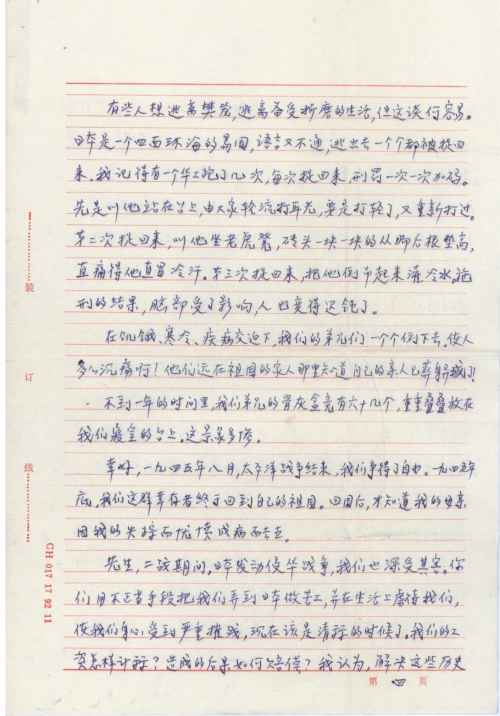

Some laborers attempted to flee from this prison and the suffering there, but it was not easy. Japan is an island surrounded by the sea, and there was a language barrier. Those who escaped were all caught and sent back. I remember that a Chinese laborer escaped several times. Each time he was caught, and the punishment got severer. After he was caught for the first time, he was ordered to stand on the platform and slapped by each of us. We had to slap him again if we slapped too gently. For the second time, he was put on a tiger bench. He was in so much pain that he sweated heavily as more and more bricks were laid under his heel. For the third time, he was hung upside down and cold water forced down his throat. The punishment damaged his brain and made him slow witted and dumb.

Our brothers died one by one due to hunger, cold and illness. How sad! Their families in the far away China did not even know they died in a foreign country!

In less than a year, over 60 Chinese laborers became cremation urns, piled up on the balcony of our dormitory. How tragic was that!

Fortunately, the Pacific War ended in August 1945 and we won freedom. We returned to China at the end of 1945. It was not until then that I knew my mother died of illness caused by worry and anger due to my disapperance.

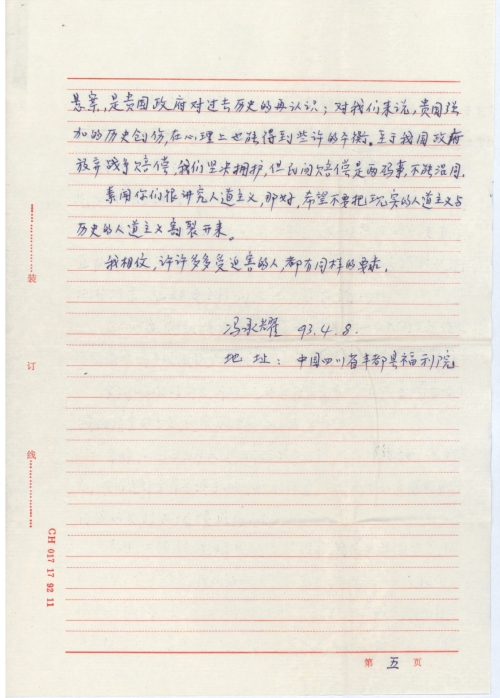

Mr. Ambassador, Japan launched the war of aggression against China during World War II and we suffered greatly from it. You used improper means to lure us to perform hard labor in Japan and tortured us. We were severely abused both physically and mentally. Now it is time for settlement of the score. How to calculate our wages? How to compensate for the consequences of your acts? I think solving these historical issues will help your government relearn history. To us, such redress perhaps can help your country achieve a better psychological balance despite the historical destruction forced on us. We firmly support our government’s decision of giving up war reparations, but civilian compensation is an entirely different matter from that. The two matters should not be confused.

I always heard that you value humanitarianism. Then, do not separate today’s humanitarianism from the humanitarianism of the past.

I believe that many, many other victims have the same demand.

Feng Chengyao

April 8, 1993

Social Welfare Institution, Fengdu, Sichuan