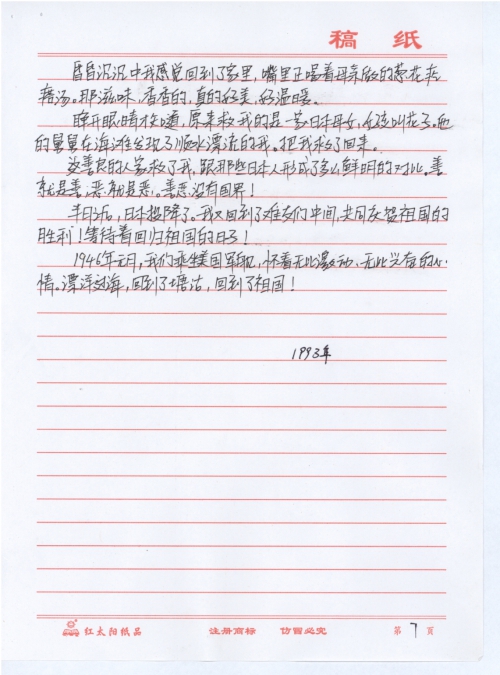

Date of letter:1993

Address of author:Beijing City

Date of event:1944

Location of event:Beijing City

Name of author:Li Liangjie

Name(s) of victim(s):Li Liangjie

Type of atrocity:Slave Laborers(SL)

Other details:I was born in Beijing in 1930. When I was 14 years old, a group of Japanese soldiers suddenly broke into my house, arrested me and threw me in a car. Dozens of other people were also captured and we were escorted to Japan to do labor work. We were given sour meals, however, we had to devour that because we were really hungry. As a result, in less than three days I got colon inflammation and hematuria and fell into a miserable situation. I almost died for several times doing labor. One day I was digging wild vegetables, when I was caught by the Japanese, who chased me with their dog. I had nowhere to go but to jump off the cliff in front of me, fearing of the consequences I would have to face if I got caught again. I swimmed in the sea for a really long time, got exhausted and then fainted. I woke up to find that a Japanese mother and daughter had saved me. They were so different from those Japanese invading our country. Note: this letter was personally delivered to Tong Zeng without an envelope

Li Liangjie Was Captured to Become Laborer

I am Li Liangjie, the child who was captured by the Japanese Army to work as a slave laborer when I was only 14. My native place is Dachao Village, Neihuang County, Henan Province, this year I’m 65.

My father is Li Lansuo, who traveled north and south across the country, and is a very capable farmer with strong sense of righteousness. Since age 12 he began to work for the livelihood of the family, throughout his life he had done many good deeds that benefited the nation and the people, and received many praises. In 1928, my father took my mother to run away from famine to Beiqitong Village, Xinle County in Hebei. He took advantage of his good relation with a friend in the “Rush into Manchuria” tide, rented ten mu of waste land from a landlord, and built a number of earth houses, later he developed the land into good vegetable garden. In 1930, I was born on this land where my father and mother worked diligently. This place is the home of my childhood, which left many fond memories of my younger days, and of course some past incidents that are unbearable to recall.

Two days before the Mid-autumn Festival in the year when I was 14, when irrigating the field, I was captured by the Japanese soldiers, bound with rope and tossed onto a truck, which took me to the then East Changshou Railway Station. At the time of my arrival there was a train from Shijiazhuang stopping over, and I arrived in Beijing at night. The puppet policemen on the train urged us several dozen men to leave the train. We were bound again, and formed a line to march to Dongjiaomingxiang. Without food and water for one day, we were locked in a room stuffed with black coal, we were cold and hungry, and were overcome with fear.

The next day, the puppet policemen delivered steamed bread and water. After we finished breakfast, we were again bound and sent to the railway station, where we boarded a box car. The train finally stoped at Tianjin Tanggu. We were forced to walk into a cold warehouse in the Japanese era. There were a number of wooden board houses, guarded by some special personnel. They were dressed in black uniform, and worn red arm band marked with “Security” wording. Each of them carried a 90 cm long wood stick, with round handle and square lower part.

We were asked to form a double-row formation to walk into the wood house, on each side of the door stood a puppet policeman armed with wood stick. Everyone walking into the door would receive one or two strikes. The house was flanked by big wooden beds on both sides, with an aisle in the middle. Each bed could accommodate 100 persons to sleep. The head policeman asked us to undress and get onto the bed. All the clothes were taken away, with only shoes and waistband left behind. He also kept shouting: “Lie down everyone. Do not talk with each other. Do not speak. Report to me, if you want to go to toilet. No one can go out without permission.”

At midnight, the big wooden bed on which we slept collapsed. I was pinned underneath the bed, and couldn’t move. It was very painful being trapped there. Finally I struggled to liberate the upper part of my body, but my leg was still trapped. It was with the help from others that I finally managed to extricate myself from the bed.

When the day broke, my legs hurt very much. At this moment the puppet policemen delivered several bundles of black clothing, and issued one set to everyone. The waistband and shoes were still our own.

Then, they led us to the kitchen, where everyone collected one empty bowl and one wotou (steamed black rice bun). We received soup with the bowl. Regardless of the quantity being given, one must walk away immediately, or to face beating. The wotou was actually made of mildewed corn flour. The taste was pungent, bitter, and mushy. Yet being really hungry, we couldn’t care much, and wolfed it down. As it turned out, in less than three days, the bowel was inflamed, with pus in stool and blood in urine. The intestine and stomach ached badly and painfully beyond words. As a result there’s a popular saying at that time: Tanggu Labor Camp, camp of death, if one could live for more than seven days, you were really blessed.

When I went to the toilet for the first time (enclosed by reed mat), two people stumbled in and stopped in front of me, then pleaded desperately. One of them called me little younger brother, another called me little elder brother. They said to me in unison: “Don’t urinate onto the ground, urinate into our mouths, we are dying from thirsty.” I was startled, and visibly shaken. It’s really incredible the situation had deteriorated to such degree that fellow sufferers were desperate to drink urine. This is absolutely a living hell.

On the fourth day, a group of captured soldiers were sent to Tanggu Labor Camp, among them one was an officer wearing yellow woolen cloth uniform. Noticing that his compatriots lying around, especially me, a child who was barely breathing, he said to his soldier: “That poor child was also detained here! Go and give him some water.”

The soldier shook the water bottle, said: “Battalion Commander, there’s not much water left, and you haven’t taken medicine.”

The Battalion Commander ordered: “Forget about me, give him water.”

The junior soldier held my face upright and said: “Young brother, drink some water.”

With eyes closed, I opened my mouth, and felt a stream of coolness rushed into my mouth, sweet, delicious, soothing, just like refreshing nectar.

As I regained consciousness, I opened eyes, and said weakly: “thank you, thank you.”

Seeing that I had become conscious, the junior solder said happily: “He’s alive, he’s alive!” Excitement aside, he didn’t forget to give the remaining water to other dying people. Less than half bottle of water saved the life of seven to eight people.

After that, the junior soldier took the water bottle and ran toward the kitchen. He saw a donkey pulling a water cart, and was walking toward the kitchen. There’s a hole on the cart which was sprinkling water away, just like a child peeing, so he leaned onto the cart with one hand, and held the bottle to take water with another hand. He drank a few mouthfuls after the bottle was full, then refilled it again, and then returned to the room to feed water to other fellow sufferers. At that moment he was already sweating profusely.

The second time, the junior soldier never returned after going out to fetch water. We found his body beside the water tank. He was killed by the Japanese in his effort to save more compatriots. His brain matter was splashed on the ground, with one hand still clutching the crashed water bottle. It’s really a horrible scene. This scene became a permanent scar left in my mind, which is indelible, unforgettable for the rest of my life.

On the fifth day, we boarded a ship named “Kuroshio Maru”. The ship slowly started with our fellow sufferers onboard, wafts of black smoke from the funnel spilled into the sky, shrouded the sea surface, and covered up the otherwise beautiful scenery. Standing on the deck, watching the billowing waves, thinking over our mishaps, missing parents back in the hometown, worrying about the fate of my country, a wave of deep sadness welled up in my heart. I couldn’t help but shed heart-rending tears. I had no idea when I could return to the motherland, when I could return home, and whether or not I could see my parents again.

Three days later, a typhoon swept in our path. Instantly the whole sea turned into terrifying waves. Swayed to and fro amid waves, Kuroshio Maru appearing so tiny and weak under Mother Nature, had to stop and cast anchor. For those already feeble fellow sufferers, they could not possibly withstand such rough tumbling. Anything just eaten were all thrown up. Many people passed out. We again had to encounter another brush with death.

When the ship set sail again after the waves settled down, the Japanese, now dressed in white overcoat, with walnut thick wood stick in hand, ordered us to go out of the cabin. Most of the 500 plus people left the cabin; about seventy to eighty people were nearly dying, and were dragged onto the deck. The Japanese one by one checked those fellow sufferers lying on the deck, they talked in a language we could not understand, and used wood stick to knock the laborers lying on the floor. If the laborer being knocked was unable to sit up, he would be directly thrown into the sea.

As the Japanese approached me, my town fellow Wang Guozan hurried to help me sit up and said: “Wake up, young brother, wake up!”

The Japanese said: “Must be dead.”

At this moment, the crowd erupted into turmoil, everyone said in chorus: “No, no, still alive.” Someone cried: “They are trashing human life. Let’s fight them to death.” The Japanese also panicked. Afraid to stir up crowd rage, they stopped throwing anyone alive overboard again. By then a total of 17 persons had been thrown into the sea.

People began to help each other by feeding water, and feeding rice. We once again escaped death.

After seven days and seven nights, Kuroshio Maru reached Moji Port, Fukuoka Prefecture in Kyushu, Japan. When we landed, we were taken to a bathhouse to have a bath. The clothing we took off was bundled with waist band, which were then lifted with 2-meter long iron hook into steam box by the Japanese for high temperature disinfection.

After taking a shower, we re-boarded the train, about one hour later we arrived at the third pit of Tagawa City Mine in Fukuoka Prefecture. Here we saw rows of newly built wooden houses. My group of 297 persons were assigned to the third row houses and slept on upper and lower berths. The breakfast was a bowl of cabbage soup or daikon soup, and one steamed bun. The lunch was two steamed buns plus water, two finger-size pickled vegetables. We were grouped into brigade, squadron and squad. Everyone was assigned a number. I was numbered six: “Lokuban” in Japanese. The uniform has a number on the chest, and a 5 cm wide red cloth band on the back.

After twenty days of training on how to line up, how to use tools, what posture to use during operation, we entered the mine. We rode a lift to enter the mine, from the opening to the bottom, and followed the pathway to reach the coal-mining spot. It took about 1.5 hours. The Koreans would punch holes and set up the detonator. The Chinese would pulverize the coal, and shovel the coal onto conveyor belt to transport it to the tank car.

Three months later, people again were too starved to move around. Many were confined into patient wards, where patients could only get half of their ration. Those already suffered from starving soon deteriorated. Death rate rose sharply. The dead were carried to slope and forest for cremation. The ash boxes were stored in the Fourth Row Room.

One day during work, my foot was accidentally punctured by a large nail, and I was also thrown into the patient ward.

Several dozen people were lying in the patient ward. Hearing my arrival, they stretched their hands, and opened mouth to whisper feeble words: “hungry, hungry.” I felt miserable, but I could do nothing.

I didn’t know whether or not I would die, or whether or not I could survive? So, I began to miss home, miss father and mother, miss my younger brothers and younger sisters, missed my child bride Liu Liu. I shed tears as I reminisced them, and cried the whole night.

In the morning, despite the foot injury I found the Korean uncle who tended to the boiler, and asked him: “How long have you been here?” He replied: “Seven years.”

I said: “Don’t they let you go after three years?” He said: “Impossible, someone have been here for eight years, and are not allowed to go back. Go take a look at the rooms in Row Four.”

So I found the rooms in Row Four, there were many gunnysacks which were piled very high, some gunnysacks had decomposed due to long years of storage. What were exposed underneath the fabric was startling human bone ash. I felt a chill running down my spine, thinking that these might be the ashes of Koreans. Perhaps this is also the destiny for us in the future. I cried another whole night.

On the second day, I really wanted to die. I would rather end my life instead of living so miserably. I approached a cliff, and found bare earth under the 10 meter deep cliff. If I jumped down chances were I might not die, and I had to suffer. So I walked around, and found a place on the cliff whose bottom was covered by piles of rocks. Figuring death would be certain if I jumped from there. I was ready. I had made up my mind. I must die.

Right at that moment, someone unexpectedly grabbed me from behind, and said: “little brother, you must live on, and must survive. You are still young, we expect you to bring our ashes back. Your parents also are looking forward to seeing you return and enjoy lives together.” Hearing their words, I no longer wanted to die, but I still missed my home like before, and cried whole night like before.

I later contracted skin illness, with festering ulcer all over the body. It’s terribly itching. At this time, an old man from Shandong named Gu Guoliang found a kind of herb on the mountain slope, and he used handkerchief to tap it softly and poultice it on my wound. Instantly I felt much better as it created a cooling effect.

Several months later, under the attentive care of several old men, I recovered nearly completely.

In order to earn more food to eat, I returned to the workplace. The Japanese assigned me to watch the winch, there’s signal light, I only needed to stop at red light, and go at green light. Since work was easier than before, I managed to stick to the post.

At this time, a number of the slave laborers had died. I saw one laborer named Zhao Guangqian was captured after escape. He said he survived by eating stolen vegetables on the field.

Only then did I know that one could survive outside, so I climbed over the dregs hill and escaped. In the rubbish heap beside a temple on the mountain, I found several orange peels, and I put them into mouth and chewed, it’s sweet, and really nice.

Later I dug vegetables in the vegetable field, and lived four to five days in this way before my luck ran out, I was discovered by the Japanese.

The Japanese chased me with hounds. Ahead was a cliff, and beneath the cliff was the sea. I had no way to go, no place to escape even if I had wings. I knew the consequences of being captured. Thinking of that, I jumped into the vast sea, and disappeared into the waves……

I had no idea how long I swam, despite my superior swimming skills, I was exhausted and fainted.

In unconsciousness I felt as if I had returned to home, and was drinking chopped scallion dough drop soup cooked by my mother. The flavor was aromatic – it’s really nice, and cozy.

After I opened my eyes, I found that a Japanese family had rescued me. The girl who tended to me was called Hanako. Her uncle found me drifting with the tide on the beach, and saved me.

This kind-hearted family saved me. What a sharp contrast with those Japanese who had persecuted me before. After all, good is good, and evil is evil. There is no national boundary to separate the good from the evil!

Half month later, Japan surrendered. I returned to my fellow sufferers, and together we celebrated the victory of the motherland! We waited for the day to come when we could return to motherland!

On the New Year Day of 1946, feeling excited and exhilarated, we rode an American warship across the ocean to return to Tanggu, and returned to the motherland!

1993